“For me, the real ‘Classic Era’ in Hollywood was the mid-1930s until about 1959,” host Robert Osborne said at the third annual TCM Classic Film Festival in April.

Coincidentally, those years also bookend the period during which the Motion Picture Production Code – and by extension, the Catholic Church – held unfettered sway over American movie studios and the content of the iconic films of the era. Or, perhaps it’s not a coincidence.

As many film fans know, “The Code” was a self-censorship doctrine instituted in 1930 by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (a trade group and lobbying association, and the forerunner of the current MPAA) in the face of controversy regarding off-screen behavior of Hollywood stars, the occasionally risqué tone of “talking pictures,” and lingering fear of government intervention. As the first president of the MPPDA, former Republican National Committee chairman and Harding cabinet member Will Hays was the namesake of the initiative, often referred to as the “Hays Code.” Ironically, Hays was also one of the first people to speak on film, in a decidedly non-risqué short used to introduce the Vitaphone sound-on-disc process to moviegoers in 1926.

As many film fans know, “The Code” was a self-censorship doctrine instituted in 1930 by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (a trade group and lobbying association, and the forerunner of the current MPAA) in the face of controversy regarding off-screen behavior of Hollywood stars, the occasionally risqué tone of “talking pictures,” and lingering fear of government intervention. As the first president of the MPPDA, former Republican National Committee chairman and Harding cabinet member Will Hays was the namesake of the initiative, often referred to as the “Hays Code.” Ironically, Hays was also one of the first people to speak on film, in a decidedly non-risqué short used to introduce the Vitaphone sound-on-disc process to moviegoers in 1926.

Initially, the Production Code was an exercise in inertia, with movies that had winkingly passed muster with enforcement officials often running afoul of the individual censorship boards that dotted the nation. Frustration over the hodgepodge of regional standards, and unilateral re-editing (or outright banning) of films by local moralcrats, is hinted at in Lloyd Bacon and Busby Berkeley’s FOOTLIGHT PARADE, a Warner Bros. musical released in October of 1933. In a scene clearly designed to send a message, producer Chester Kent (James Cagney) debates the propriety of a feline-themed musical number with his censor, Charlie Bowers (Hugh Herbert).

“The tomcats and the pussycats are alright, but the kittens are illegitimate?” Cagney asks, incredulous.

“The tomcats and the pussycats are alright, but the kittens are illegitimate?” Cagney asks, incredulous.

“They certainly are!” huffs Herbert.

“Unless they’re married by a preacher cat?” Cagney adds. “No preacher cat, no kittens?”

“No, you can’t use it in 39 cities!” the censor proclaims.

Cagney’s character, a producer of the live song and dance “prologues” that helped smooth the transition from silent pictures with musical accompaniment to talkies in the early ’30s, decides to ignore Herbert and do the number anyway.

“You see that window over there?” he growls at the censor “Take a running jump. I think you can make it.”

Sadly, life did not imitate art. With the formation of the Catholic Legion of Decency in 1933 by Cincinnati archbishop John Timothy McNicholas, and the institution of their “C” (as in “Condemned”) rating for films that “massacred” American morality, the MPPDA was finally pressured into giving the Code teeth. As of July 1, 1934, every film was subject to review, revision and certification by the Production Code Administration, a dedicated office managed by Hays lieutenant (and devout Catholic) Joseph Breen. “The Hitler of Hollywood” ran the PCA (aka the “Breen Office”) for the next two decades, and was universally despised by filmmakers, and retroactively, by many current fans of old movies.

Sadly, life did not imitate art. With the formation of the Catholic Legion of Decency in 1933 by Cincinnati archbishop John Timothy McNicholas, and the institution of their “C” (as in “Condemned”) rating for films that “massacred” American morality, the MPPDA was finally pressured into giving the Code teeth. As of July 1, 1934, every film was subject to review, revision and certification by the Production Code Administration, a dedicated office managed by Hays lieutenant (and devout Catholic) Joseph Breen. “The Hitler of Hollywood” ran the PCA (aka the “Breen Office”) for the next two decades, and was universally despised by filmmakers, and retroactively, by many current fans of old movies.

Except, perhaps, by Robert Osborne.

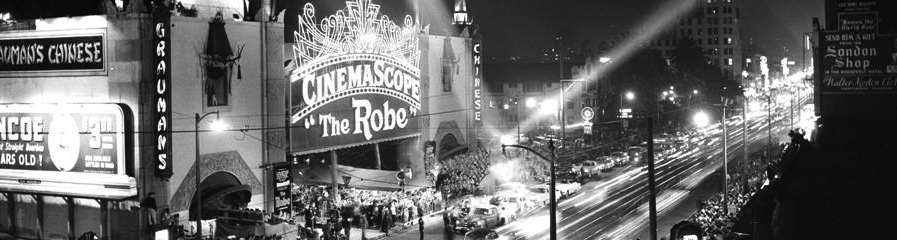

I understand what Mr. Osborne meant, of course. While he is surely no admirer of Breen’s moralistic meddling, the glitz and glamour we associate with classic Hollywood was perfected five-six years after the switch to talkies, just as the PCA’s reign of terror began. And the Code reigned supreme (with slight tinkering along the way, including the reversal of the shameful miscegenation prohibition) until the late 1950s, when the studios, in decline due in part to the competition of television, began to routinely flout its hoary conventions. Director Otto Preminger was a leader in these battles, with controversial films like THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM (1955) featuring Frank Sinatra as a heroin addict in part contributing to the rollback of regulations regarding depictions of drug abuse.

By the time Billy Wilder’s SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959) did big business with a sexier-than-ever Marilyn Monroe, two men in drag, and the implication of male-male coupling at the climax, it was clear that it was time for a change. That change finally came in 1968, when Breen successor Geoffrey Shurlock stepped down, and the MPAA instituted the letter-based rating system.

That Osborne’s historic benchmarks for classics coincide with an era characterized by fascistic censorship is likely a coincidence. Or maybe it isn’t. There is a school of thought that argues that the American film industry produced greater, more enduring art during this period than they had before or have since, in part because of these content restraints. But the tarnish left by the Code on Hollywood’s Golden Age cannot be ignored. Modern viewers may be charmed by the workarounds producers employed to evade the PCA, but regulations that encouraged racial discrimination, homophobia, sexism and political isolationism did genuine harm to the art form, and to the nation as a whole.

And before any apologist applauds the studios for shunning the sensational and embracing the timeless in 1934, remember this: every decision the collective film industry has ever made has been about the bottom line. When the onset of the Depression made discretionary cash scarce, they (occasionally) amplified the lurid to sell tickets. When bans and boycotts by Christian (and subtly anti-Semitic) pressure groups threatened ticket sales, they embraced the traditional. And when it made good financial sense to re-liberate the medium, they transitioned to the more inclusive system still in use today.

By that point, of course, the damage had been done. Conformity had been celebrated for a generation, the cause of civil rights in America had been slowed, and a small but vocal minority had been allowed to use the most dominant and influential popular cultural medium to promote an ideology.

The more movies I watch, the more I tire of the predictable perfection – both technical and behavioral – of the films of Mr. Osborne’s Classic Era. What fascinates me more are the years that came before the Code, specifically the early days of sound, when production techniques, and depicted mores, were less precise.

Widespread attention was first brought to the so-called “Pre-Code” Era, at least in consumer marketing terms, by Forbidden Hollywood, a series of home video releases that began on laserdisc from MGM-UA two decades ago, and continued on VHS and DVD. But these sets, recently revived with two delightful new volumes by the Warner Archive Collection, have also contributed to a sometimes skewed perspective about the films of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The first three Forbidden Hollywood DVD collections, released between 2006 and 2009 by TCM, are all housed in packaging featuring archival photos of scantily clad females, and the films included are often suggestive stories of Depression Era women bartering their bodies (such as the infamous BABY FACE). I know sex sells, but it also misrepresents what I believe is so revelatory about Pre-Code storytelling. What attracts me to these films is their firm footing in the moral and ethical ambiguities of real life, particularly in times of trouble. Behavior and decision-making is often delightfully pragmatic, and issues of right and wrong lack the clear lines promulgated by Mr. Breen and his army of extremists.

Simply put: the pictures may be black and white in Pre-Code films, but the stories almost never are.

This moral and ethical pragmatism is front and center in WAC’s two new Forbidden Hollywood volumes, featuring a collection of complex protagonists engaging in refreshingly non-heroic behavior. In Volume 4: William Powell is a dashing thief courting (married) Kay Francis in JEWEL ROBBERY (1932) and a crusading attorney gone (temporarily) astray in LAWYER MAN (1932); Loretta Young is a small town girl eager to start misbehaving in New York City in THEY CALL IT SIN (1932); and Kay Francis returns as a powerful magazine editor in an open marriage in MAN WANTED (1932). Three of the four films in this set are directed by William Dieterle, and they are among his first English language films after emigrating from Germany.

In Volume 5: uber-cad Warren William is a corrupt carney in Roy Del Ruth’s THE MIND READER (1933); Barbara Stanwyck is the cutest con at San Quentin in Howard Bretherton and William Keighley LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT (1933); Joan Blondell is a nurse on the make in Lloyd Bacon’s MISS PINKERTON (1932); and James Cagney is a small time hustler who makes good in Mervyn LeRoy’s HARD TO HANDLE (1933).

In both sets, mature themes abound: murder; marrying for money; robbery; non-traditional love relationships; crime cover-up; drug use; under-age sex; ridicule of religion; sleeping with the boss; and fraud. LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT alone features gangsters, sympathetically depicted killers, a madame, a prostitute, and a cigar-smoking female inmate who likes to “wrestle” with other women. While comeuppance is occasionally meted out for non-conformity, more often it is not. “Last reel conversions” are also the exception, not the rule.

These films, with their seemingly anachronistic depictions of sex, vice and anti-heroism, force viewers to reassess the concept of “classic,” and to further scrutinize the spurious version of early 20th Century history created for us by the studio system. Plus, with their fast pace (running times are usually around an hour) and shockingly frank dialogue, they positively crackle with vitality. As the trailer for MAN WANTED proclaims, they are “Spicy! Snappy! Sparkling!”

Owning (I assume) to the library it controls, WAC’s new Forbidden Hollywood releases all come from the parent company and its subsidiary, First National Pictures (acquired in September, 1928). With their gritty urban settings and blue collar sensibilities, Warner Bros./First National was arguably the preeminent producer of Pre-Code pictures, but they weren’t the only game in town. All the studios dipped their toes into this sometimes turgid pond, and those offerings are represented in other worthwhile sets, all readily available and recommended. Films from MGM and Universal are included on the first three Forbidden Hollywood sets, and TCM recently released the Columbia Pictures Pre-Code Collection, with five titles – two including Warner favorite Barbara Stanwyck (a non-exclusive contractee at both studios). Universal’s Pre-Code Hollywood Collection includes six Paramount films from 1931-34, all currently controlled by Universal.

Whenever I hear someone condemn old movies for being boring, fake or dated, I always suggest they watch a Pre-Code. While these films may not be as polished as GONE WITH THE WIND, CASABLANCA or BEN-HUR, they are no less “classic.” In a sense, they are more timeless than many of the later, better known favorites, because they remind us that human beings have always been complex creatures. In that regard, my idol Robert Osborne and I may have to agree to disagree.

***

Forbidden Hollywood Collection Volume 4

Format: Made To Order (M.O.D.) DVD

Quantity: 4 discs/1 film per disc

Special Features: original trailers for MAN WANTED, JEWEL ROBBERY and LAWYER MAN

All titles have remastered picture and audio.

1) MAN WANTED (1932)

Release date: April 23, 1932 Duration: 62 minutes

Director: William Dieterle Producer: uncredited

Writer: Robert Lord (story), Charles Kenyon (adaptation)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: Kay Francis (Lois Ames), David Manners (Tom Sherman), Una Merkel (Ruthie Holman, Tom’s fiancée), Andy Devine (Andy Doyle), Claire Dodd (Ann Le Maire, Freddie’s girlfriend), Elizabeth Patterson (Miss Harper, the secretary), Kenneth Thomson (Freddie Ames), Edward Van Sloan (Mr. Walters, French & Sprague manager), Frank Coghlan Jr. (Kid in store), Charlotte Merriam (Miss Smith, the receptionist)

Synopsis: “Freedom is the only basis for a successful marriage,” polo-playing layabout Freddie Ames (Kenneth Thomson) tells wife Lois (Kay Francis), editor of a national style magazine. “I know how I’d feel if you made me stop the things I like.” One of the “things” Freddie likes is Ann Le Maire (Claire Dodd), and Lois soon counters with a dalliance of her own, with her private secretary Tom Sherman (David Manners). This doesn’t sit well with Tom’s fiancee Ruthie (Una Merkel) or his best bud Andy (Devine). Can this story end happily? Of course it can. Because this is Pre-Code.

Notes: MAN WANTED was Kay Francis’ first Warner Bros. starring vehicle, and it’s got everything I love about her: sexy, smirky glances; beautiful costumes; and an almost feral sensuality. Unlike later leading ladies, Francis looked like she might actually enjoy sex, and seek it out when possible. The Warner Bros. marketing department must have agreed with me on that, because the trailer begins with Kay dropping her shear bathrobe, and slinking into bed with a come-hither grin. Plus, the film is chock-full of quotables, like: “I didn’t trail you up to Bar Harbor just to dance with you!” And, “Will you play bridge or make love or something? Just let me sleep!” Like many great Pre-Codes, it’s set in New York City (via Burbank) and also features wealthy hobnobbing at lavish country estates. Plus, it’s shot by CITIZEN KANE cinematographer Gregg Toland, and it looks like it. Grade: A+

2) JEWEL ROBBERY (1932)

Release date: August 13, 1932 Duration: 68 minutes

Director: William Dieterle Producer: uncredited

Writer: Erwin Gelsey (screenplay), Ladislas Fodor (original story), Bertram Bloch (English version)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: William Powell (The Robber), Kay Francis (Baroness Teri von Hohenfels), Helen Vinson (Marianne, Teri’s friend), Lee Kohlmar (Mr. Hollander, owner of the jewelry shop), Hardie Albright (Paul), Spencer Charters (Lenz, of the Vienna Protective Agency), Clarence Wilson (Polizei Prasidenten), Alan Mowbray (Fritz, the detective), Henry Kolker (Baron Franz von Hohenfels), Charles Coleman (Charles, The Robber’s butler/henchman), Ruth Donnelly (Berta, Teri’s maid)

Synopsis: “In the morning, a cocktail. In the afternoon, a man,” married Viennese Baroness Teri (Kay Francis) says to her friend Marianne (Helen Vinson). Teri is betrothed to the Baron Franz, an older gent who enjoys nothing more than buying baubles for his beautiful young wife. On one such excursion they run into The Robber (William Powell), a smooth criminal intent on liberating the Hollander Jewelry Shop of everything valuable and shiny. He also takes a shine to Teri, and makes an enticing suggestion: “Night is before us and, if you wish, at dawn we shall have a secret behind us.” Teri’s reply: “Let’s not be in such a hurry. There are so many pleasant intervening steps.” Guess where the two of them end up?

Notes: Warner Bros.’ attempt at a “continental comedy” is sort of like a rough-hewn TROUBLE IN PARADISE (released two months later, by Paramount). This movie has become (in)famous for extended scenes of pot smoking, which was still technically legal in 1932. Much as I enjoy seeing forbidden behavior of all sorts in Pre-Code films, these scenes are some of my least favorite. The silly, stoned behavior is one joke that does not keep giving, and takes away valuable screen time from one of the great screen duos of the 1930s: William Powell and Kay Francis. In their fifth film together (between Paramount’s LADIES’ MAN and Warners’ ONE WAY PASSAGE), Powell and Francis are like a flawless gem. Warner contractee Helen Vinson makes her film debut here. She’s got three films in this set alone, proving that the brothers Warner liked to start them off fast. Sexy and fun. Grade: A

3) THEY CALL IT SIN (1932)

Release date: November 5, 1932 Duration: 69 minutes

Director: Thornton Freeland Producer: Hal Wallis (uncredited, per IMDB)

Writer: Lillie Hayward and Howard J. Green (screenplay), Albert Steadman Egan (novel)

Studio: First National

Cast: Loretta Young (Marion Cullen), David Manners (Jimmy Decker), George Brent (Dr. Tony Travers), Una Merkel (Dixie Dare, a “specialty dancer”), Helen Vinson (Enid Hollister), Louis Calhern (Ford Humphries), Joe Cawthorne (Mr. Hollister), Nella Walker (Mrs. Hollister), Elizabeth Patterson (Mrs. Cullen, Marion’s mother), Erville Alderson (Mr. Cullen, Marion’s father), Marion Byron (Soda Jerk in Kansas), Miki Morita (Moto, Jimmy’s butler), Roscoe Karns (Brad, rehearsal director)

Synopsis: “It’s time to put you in your place,” mom (Elizabeth Patterson) tells small town daughter Marion (Loretta Young) when she comes home late from a date with visiting city slicker Jimmy Decker (David Manners). That “place” ends up being New York City, where Marion surprises Jimmy, with suitcase in hand. But there’s another surprise: Jimmy’s fiancée, Enid Holister (Helen Vinson). Plucky songwriter Marion goes to work for producer (and casting couch devotee) Ford Humphries (Louis Calhern) and learns how to smoke, and do other things that are frowned upon in the sticks. When Humphries takes a drunken dive off his penthouse balcony, it’s curtains for Jimmy – unless Dr. Tony Travers (George Brent) can save the day.

Notes: I often ridicule female fans who sexualize long-dead male classic film stars, but Loretta Young? Hubba hubba. And the best thing about this movie is, we literally have no idea which guy she will end up with until the last 60 seconds. There’s lots to like in this romantic potboiler: Manners macking on Young in church; Una Merkel cavorting about in her slip; and beloved character actor Roscoe Karns as a harried rehearsal director. Only negative: with both David Manners and George Brent in the same movie, we’re reminded that Warner Bros. leading men during this era couldn’t match the luminance of their leading ladies. Both are handsome but not particularly memorable, and that may be the way Warners wanted it. That’s another reason to love Pre-Code – the ladies were clearly in the lead. Grade: B+

4) LAWYER MAN (1933)

Release date: January 7, 1933 Duration: 68 minutes

Director: William Dieterle Producer: uncredited

Writer: Rian James and James Seymour (screenplay), Max Trell (novel)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: William Powell (Tony Adam), Joan Blondell (Olga Michaels), David Landau (John Gilmurry), Helen Vinson (Babs Bentley, sister of Granville Bentley), Claire Dodd (Ginny St. Johns), Kenneth Thomson (Dr. Frank “Frankie Snookums” Gresham), Allen Jenkins (Izzy Levine, a hood), Alan Dinehart (Granville Bentley), Tom Kennedy (Jake the Ice Man), Sterling Holloway (Olga’s drinking buddy), Roscoe Karns (Merritt, a reporter), Milton Wallace (Judge Wilson), Jack La Rue (Spike Murphy, a hood)

Synopsis: “I was raised in the streets,” Lower East Side legal eagle Tony Adam (William Powell) says to shady character Izzy Levine (Allen Jenkins) as he decks him. Adam soon tires of the rough and tumble life in Lower Manhattan and moves on up to a fancy firm with his loyal secretary Olga (Joan Blondell) in tow. When he gets on the wrong side of political boss Gilmurry (David Landau) and is set up for a fall, only his street smarts can save him.

Notes: One of the most elegant male stars of the ’30s as a former street tough? I don’t buy it, but I’ll go pretty much anywhere with Bill Powell, even to the dark side. There’s lots to like here, including BOTH Helen Vinson and Claire Dodd (who look like twins), and an all-star team of supporting players (Blondell, Landau, Jenkins, Holloway, Karns, La Rue) in small but memorable roles. My only knock on the film is its slight tonal inconsistency, veering from relatively straight drama into light comedy in the last third of the film. This film has a lot in common with another Pre-Code legal drama THE MOUTHPIECE (1932) starring Warren William. If it had taken the darker turn that film took, I might have liked it better. LAWYER MAN may be the fourth-best film in this set but, considering how good the others are, that’s still pretty high praise. Grade: B+

Forbidden Hollywood Collection Volume 5

Format: Made To Order (M.O.D.) DVD

Quantity: 4 discs/1 film per disc

Special Features: original trailers for MISS PINKERTON, HARD TO HANDLE, and LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT

All titles have remastered picture and audio.

1) MISS PINKERTON (1932)

Release date: July 30, 1932 Duration: 66 minutes

Director: Lloyd Bacon Producer: Hal Wallis (uncredited, per IMDB)

Writer: Niven Busch & Lillie Hayward (adaptation), Robert Tasker (additional dialogue), Mary Robert Rinehart (novel)

Studio: First National

Cast: Joan Blondell (Nurse Georgia Adams, aka ‘Miss Pinkerton’), George Brent (Police Inspector Patten), Ruth Happ (Paula Brent, the victim’s girlrfriend), Lyle Talbot (reporter), Elizabeth Patterson (Juliet Mitchell, aunt of victim), C. Henry Gordon (Dr. Mitchell), Holmes Herbert (Arthur Glenn, family lawyer), Blanche Friderici (Mary, Juliet’s maid), John Wray (Hugo, the butler), Don Dillaway (Charlie Elliott), Sherry Hall (Paula Lenz, the police stenographer)

Synopsis: “I’m beginning to envy the patients. At least things happen to them!” complains bored nurse Georgia Adams (Joan Blondell). She’s soon wishing for a return to her drab routine, when she find herself assigned to care for the elderly aunt of a shooting victim. Herbert Wynn, heir to the Mitchell family, has been found shot to death in an apparent suicide, and there’s a little matter of a $100,00o insurance policy. The handsome rookie inspector assigned to the case (George Brent, again) unofficially deputizes Georgia and christens her “Miss Pinkerton of Scotland Yard.” Soon, the nurse is wandering dark corridors, dodging shadowy figures, and discovering all manner of secrets. All the participants end up together in a room at the end, and the killer is revealed – proving that what Columbo was doing in the 1970s was nothing new.

Notes: This is the headscratcher of the set, with precious little that can be considered “Pre-Code,” other than Blondell striping down to her skivvies in the nurse’s dorm. MISS PINKERTON starts out feeling like William Wellman’s NIGHT NURSE (1931), with sassy girls in uniform cracking wise, but quickly transitions into a ho-hum “old dark house” whodunit. Still, Blondell as the man-hungry leading lady, spouting slang like “make it snappy” is delightful. Production-value-wise, this is also the roughest of the bunch. There’s a certain charmingly rushed quality to the proceedings, with at least three flubbed lines from Blondell, nonexistent sound effects (like a phantom door knock), and missing reverse shots on a number of two-way conversations. A handful of pieces of off-camera dialogue are virtually inaudible, even with WAC’s truly remarkable audio clean-up. Blondell and Brent have nice chemistry, though, and it would have been fun to see them continue as partners in a series. Grade: B

2) HARD TO HANDLE (1933)

Release date: January 28, 1933 Duration: 78 minutes

Director: Mervyn LeRoy Producer: uncredited, per IMDB

Writer: Houston Branch (original story), Robert Lord and Wilson Minzer (screenplay)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: James Cagney (Myron C. ‘Lefty’ Merrill), Mary Brian (Ruth Waters, Lefty’s girl), Allen Jenkins (Radio Announcer), Ruth Donnelly (Lil Waters, Ruth’s mother), Claire Dodd (Marlene Reeves), Robert McWade (Charles Reeves, Marlene’s father), Matt McHugh (Joe Goetz, Ruth’s dance partner), Sterling Holloway (Andy Heaney), Gavin Gordon (John Hayden, the photographer), Louise Mackintosh (Mrs. Weston-Parks), Douglass Dumbrille (District Attorney), John Sheehan (‘Mac’ McGrath)

Synopsis: “I always knew the public was dumb, and they panned out even dumber than I thought!” smalltime con artist Lefty Merrill (James Cagney) says. After promoting a phony dance marathon with his girlfriend Ruth (Mary Brian) set up to win the $1,000 prize, Lefty’s partner Mac (John Sheehan) steals the money, and Lefty is forced to hustle to prove himself to his girl and her gold-digging mother, Lil (Ruth Donnelly). Our hero wears out his welcome in Southern California, and follows Ruth and her mom to New York, where he finally hits the jackpot. But his big score is a set-up, and Lefty ends up holding the bag on a shady land deal. Locked up for fraud, Lefty runs into Mac, who gives him an idea: what better way to sell grapefruit farms to the suckers than by creating a grapefruit diet craze? For once, his scheme finally pans out, but is it too late to win back his girl?

Notes: Mary Brian gets second billing here as Cagney’s girlfriend, but his real co-star is Ruth Donnelly as his money-obsessed prospective mother-in-law. Donnelly, a Warner contractee and frequent bit player, is given the best lines in the film, all having to do with her desperate search for a rich son-in-law. “All bridegrooms are slightly used,” she tells her daughter when she finds her boyfriend in a clinch with another girl. “We’re sneezing away a fortune!” There are a lot of in-jokes as well, with Cagney once again cast as a sharpie (as in BLONDE CRAZY, released a year earlier) and the plot turning on grapefruits, a reference to his famous fruit assault in THE PUBLIC ENEMY (1931). Just about everyone in this movie is a hustler which, to me, is what Pre-Code is all about. For my money, Cagney was never more fun to watch than in these early ’30s pictures. He may have refined his craft in later years, but in the early 1930s he defined the art of acting of talkie acting. Grade: B+

3) LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT (1933)

Release date: February 4, 1933 Duration: 69 minutes

Director: Howard Bretherton, William Keighley Producer: Raymond Griffth (uncredited, per IMDB)

Writer: Brian Holmes & William McGrath, Sidney Sutherland (screenplay), Dorothy Mackaye & Carlton Miles (play)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck (Nan Taylor), Preston S. Foster (David ‘Fighting Dave’ Slade), Lillian Roth (Linda, Nan’s friend at San Quentin), Maude Eburne (Aunt Maggie, the madame), Ruth Donnelley (Noonan, the matron), Dorothy Burgess (Susie, Nan’s rival), Harold Huber (Lefty), Don (Lyle Talbot), Madame Sul-Te-Wan (Mustard, a fellow inmate), Robert Warwick (Warden)

Synopsis: Bad girl Nan – daughter of a church deacon – is an accomplice in a bank stick-up, and nearly gets away with it, thanks to the unwitting help of radio reformer (and childhood friend) ‘Fighting Dave’ Slade. She ends up in the pokey, where she is taken under the wing of Linda, a jaded inmate locked up for killing her husband. The two unite against Susie, a self-righteous acolyte of Slade, who torments Nan with reminders of the man she loves. When Nan gets out she goes right to Slade to settle a score, and ends up in his arms – but not before trying to kill him. Such are the ambiguities of life before The Code.

Notes: This may be the most prototypically Pre-Code film in the set. For 65 minutes, it’s a textbook example of the genre, then Barbara Stanwyck has an eleventh hour conversion, and it all goes to hell. And by “hell,” I mean a happy ending. That said, Stanwyck is at her sneering, sarcastic best throughout this film, holding her own against all manner of shady characters. Drawbacks: the woman’s ward at maximum-security San Quentin is made to look like a school for wayward girls, and the likelihood that male convicts could burrow their way directly into a female inmate’s cell is pretty non-existant. But, other than that, there’s a nice sense of realism at work here. There’s also a significant sequence where a black inmate (Mustard, played by actress credited as Madame Sul-Te-Wan) dresses down a white inmate, and stands up for her rights. Like with Theresa Harris (as Chico, Stanwyck’s partner in crime) in BABY FACE (1933), this scene hints at the impact the movies might have had on civil rights, had they not relegated African Americans to domestics, porters and bug-eyed comic relief. Another similarity with BABY FACE: both use W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues, the unofficial “Pre-Code theme,” over the opening credits. Finally, according to IMDB, the uncredited producer of LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT was Raymond Griffith, the former top-hat-wearing silent comedian who transitioned to a career behind the camera in the 1930s. Grade: A

4) THE MIND READER (1933)

Release date: April 1, 1933 Duration: 70 minutes

Director: Roy Del Ruth Producer: Hal Wallis (uncredited, per IMDB)

Writer: Robert Lord and Wilson Mizner (screenplay), Vivian Crosby (play)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Cast: Warren William (‘Chan’ Chandler aka ‘Chandra the Great’), Constance Cummings (Sylvia Roberts), Allen Jenkins (‘Frank’ Franklin, Chan’s accomplice), Mayo Methot (Jenny), Clarence Muse (Sam, Chan’s accomplice), Natalie Moorehead (Mrs. Austin), Earle Foxe (Don), Fred ‘Snowflake’ Toones (Hair tonic customer), Robert Grieg (Carnival swami)

Synopsis: “Tie a bath towel around your head and tell the chumps what they want to hear!” low-rent grifter Chandler (Warren William) proclaims to his good-natured, but not-too-bright accomplice Frank (Allen Jenkins). Soon Chandler becomes ‘Chandra the Great’ and starts raking in the dough as a carnival fortune teller. Along the way he meets Sylvia (Constance Cummings), a young woman yearning to escape her small town. She goes to work for Chan, and eventually discovers his act is a fake. Sylvia convinces him to go straight, and they move to New York, where Chan becomes a brush salesman. But Frank lures him back into the phony mentalism business, with dirt on the swells he’s been working for as a limo driver. Chan rats out the cheating husbands of New York City to their gullible wives, until one of the unhappy hubbies threatens him and is shot in the struggle. Chan escapes to Mexico, and Sylvia is arrested for the crime. But his conscience gets the better of him, and ‘Chandra’ comes back to face a less-than-great prison stretch.

Notes: Erudite scoundrel Warren William is arguably miscast in this movie as a smalltime carney, but he makes the best of it (even though I never believe him when he says ‘ain’t’). This was one of the great things about the studio system – you used the players you had on your bench. Case in point, Allen Jenkins, who was just as at home playing Izzy Levine in LAWYER MAN as he was playing Frank Franklin in this film. Like LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT, THE MIND READER suffers from the main character’s attack of conscience in the final minutes of the film. One of the things I enjoy most about Pre-Code is the occasional unapologetic villainy of certain characters, particularly those played by Warren William. I wish this character had not been redeemed. But I’m pessimistic like that. Grade: B+

This was as fantastic as I had expected, Will, really enjoyed it!

Especially well put: “What attracts me to these films is their firm footing in the moral and ethical ambiguities of real life, particularly in times of trouble.”

I get what you’re saying about the pot smoking in “Jewel Robbery,” but at the same time it is a perfect example of the unexpected, bizarre places these films could sometimes go. Would “Jewel Robbery” have been better without it? Sure, but the holy crap! moment it provides holds up for me upon repeated viewings. This seems like someone’s pet idea that was going to find its way into one project or another and “Jewel Robbery” was it! And it helps me love the movie all the more!

Interesting to see you mention Warren William in relation to “Lawyer Man”–this is one of the top couple of William Powell Warner Brothers movies that I think Warren would have fit in better than Powell. I feel that way about a lot of Powell’s pre-MGM talkies though. If the character isn’t urbane (anyone not use that word discussing Powell?), William often seems a better down and dirty fit to me. I am biased.

Well, the Code might not be enforced during this period, but I’m betting if those “attacks of conscience” weren’t there in the end our lead characters would likely have to die. You’ve mentioned to me that Warren William seems to die an awful lot in his films–that’s because, code or not, he’s often an unrepentant bastard who even in pre-code times must still pay a price before the end of the movie.

I’m glad to see you mention the pre-code sets put out by other companies as well. I think, largely due to TCM’s library and exposure, these Warner/First National films are really taking over what it means to be pre-code. You know Warner filled their movies with sluts, but at the other end of the spectrum Paramount could be really sexy (Miriam Hopkins springing to mind several times; Claudette Colbert too); We think gangsters at Warner Brothers; monsters at Universal. The TCM experience alone can really skew the definition over time (though thankfully I see they’ve FINALLY loaded up their Halloween schedule with Universal horror classics).

All that said, I think I’m with you. I prefer the ever so real sluts and scumbags that Warner Bros./First National delivered time and again during this era! Thanks for a great read!

Thanks Cliff.

I agree about JEWEL ROBBERY, but the whole time I was watching that pot sequence I wondered how Paramount would have handled it – probably with a bit more finesse, I think. Although the occasional lack of finesse is what I love about Warner Bros/First National in the early 1930s

And I agree that Warren William would have been better cast in LAWYER MAN than Powell, though I still say that neither of them seem like Lower East Side boys to me. ALthough William, with his meanness, does seem more at home in the gutter than Powell. The whole time I was watching it I was thinking, “Pat O’Brien should be playing this part.” Cagney could have done it, too. It would have been more believable with a hot-headed Irishman (though not necessarily better).

Speaking of attacks of conscience, imagine if LADIES THEY TALK ABOUT had ended with Stanwyck shooting Preston Foster fatally, and in his dying breaths discovering that he really loved her and didn’t intentionally set up her buddies. Now that would have been an ending!

Also agree on Warners basically crowding everybody out of the Pre-Code category. It’s odd, because WAC owns all the MGM titles of that era. I wonder why they didn’t include one or two to round out the set. At least one MGM title appeared in the three previous “Forbidden Hollywood” sets. Volume 2 actually had two of them (THE DIVORCEE and A FREE SOUL)

Not that I’m complaining. Warners/First Nationals are almost always better than MGMs from this era. I know you agree with me on that

Awesome post! That’s all.

Aurora

Thanks Aurora.

Great post, with many perceptive comments on the Code document and how it came into power and the thinking behind its strictures. I agree that, while Hollywood films from 1934 to the 1960s are well made and glamorous to look at, the ‘pre-Code’ (before enforcement) era movies are much livelier, more honest in their depiction of life (especially under the Depression), and more likely to appeal to audiences today.

The Warner Bros musical ‘Dames’ (which came out in 1934) is, like ‘Footlight Parade,’ a hilarious send-up of censorship, but it also seems to be a direct hit at the Breen office, with its depiction of a blue-nosed founder of a censorship group on the look-out for ‘sin’ in some great Busby Berkeley musical numbers. Warner Bros made most of the best pre-Code movies, and I think this was their way of letting us know what they thought of the Breeners!

DAMES (1934) is also a Busby Berkeley film. It’s pretty clear that he had a bone to pick with Mr. Breen!

Pingback: She Works Hard For the Money: The Columbia Pictures Pre-Code Collection on DVD from TCM | cinematically insane

Pingback: GOD’S GIFT TO WOMEN (1931) from Warner Archive: One Kiss and You Die! | cinematically insane

Pingback: Man Wanted (1932) – Charles Kenyon Updates The Office Wife (1930) — Immortal Ephemera